Topics: Culture

01.02.2006

The dynamism of its modern art has put Russia at the forefront of the

international scene. The inauguration of the First Moscow Biennale prompted an

exhibition

‘We Can Do It’ showcasing major international artists working in a diverse range of styles and

media.

Introduction*

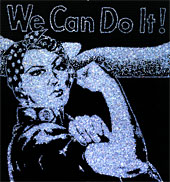

VIK MUNIZ.

ROSIE THE RIVETER

(from pictures of diamonds). 2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

127x162.5 cm.

ROSIE THE RIVETER

(from pictures of diamonds). 2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

127x162.5 cm.

One of Russia’s recent successes on the international scene has been the dynamism of its

modern art, as evidenced by a recent series in London of events and

installations by Russian artists.

In recognition of this, the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation announced in 2005 the inauguration of the First Moscow Biennale. A parallel programme of events was staged in galleries across Moscow.

The exhibition ‘We Can Do It’ was held at the Gari Tatinzyan Gallery. Curated by a commercial cultural institution with a well-earned reputation in New York and Berlin, the exhibition included eight major artists covering a broad spectrum of nationalities, styles and media. The title ‘We Can Do It’ is from a painting by Vik Muniz. Based on a propaganda poster entitled ‘Rosie the Riveter’ it relates not, as might be supposed, to Soviet propaganda but to a US propaganda campaign aimed at recruiting women workers into American factories during the Second World War.

In recognition of this, the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation announced in 2005 the inauguration of the First Moscow Biennale. A parallel programme of events was staged in galleries across Moscow.

The exhibition ‘We Can Do It’ was held at the Gari Tatinzyan Gallery. Curated by a commercial cultural institution with a well-earned reputation in New York and Berlin, the exhibition included eight major artists covering a broad spectrum of nationalities, styles and media. The title ‘We Can Do It’ is from a painting by Vik Muniz. Based on a propaganda poster entitled ‘Rosie the Riveter’ it relates not, as might be supposed, to Soviet propaganda but to a US propaganda campaign aimed at recruiting women workers into American factories during the Second World War.

One of the most dramatic shifts within the ‘art system’ during the post-war era is arguably the breaking up of genres. Since the emergence of visual aesthetics during the classical period – whether based on form, as by Aristotle, or founded on materials, as in Pliny’s Naturalis Historia – the genre system has been as set in stone as the very entry to the Acropolis in Athens suggests: a picture gallery to the left, and a sculpture gallery to the right.

ANTONY GORMLEY.

SUBLIMATE-II. 2004.

Bright mild steel blocks,

194x53x30 cm.

SUBLIMATE-II. 2004.

Bright mild steel blocks,

194x53x30 cm.

During the evolution of the visual arts, every question on what art is (or

should be), every bitter feud between ancients and moderns, every one of the

multitude of different and mutually contradictory

‘-isms’, has been argued in the context that genres, in and of themselves, have a

substantive reality. Even the theories of Marcel Duchamp, the revolutionary

practices of Italian and Russian futurists, the avant-guarde experiments with

new artistic techniques, such as collage, could do but little to challenge a

grid that so comprehensively organized what could be said and done in the field

of art. And the consequences went further than that: the laws of genre

influenced the curricula of the art academies, the architecture of museums and

exhibition halls, and the very way that money changed hands on the art market.

All that started to crumble shortly after the Second World War, and coincided,

in a more than symbolic way, with the emergence of the US, or more specifically

New York, as the new epicentre of artistic development. A few key elements in

this sea of change deserve to be noted. The emergence of the Fluxus movement,

of

‘happenings’ and Aktionen, where art is viewed as a social activity – a performance, limited in space and time, and fundamentally impossible to

reproduce. The focus upon art as an

‘irreproducible’ experience could also be found in the views of more ‘traditional’ artists such as Robert Morris. In his ‘Notes on Sculpture’ (1966) he launched a convincing standpoint that the work is nothing in or of

itself

– it appears only through the presence of the viewer in an absolute here and now,

thereby limiting the role of a specific genre as normative for the experience

of the artwork. And in Minimalism we find an aesthetic where

– in Donald Judd’s words – what constitutes its quality as a work of art is the ‘specificity of the object’, regardless of whether it be a painting, a sculpture, or some other form. Other

events were soon to follow.

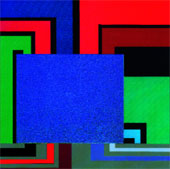

PETTER HALLEY.

COLLACATION. 2004.

Acrylic, day-glo, pearlescent, roll-a-tex on canvas,

182.5x182.5 cm.

COLLACATION. 2004.

Acrylic, day-glo, pearlescent, roll-a-tex on canvas,

182.5x182.5 cm.

If the artwork consists in its specific existence in a field of experience, then

there is no need to be limited to traditional materials. Many artists started

to work with pre-fabricated industrial materials: Dan Flavin, for instance,

with his emblematic light tubes. This trend gave rise to an erosion of the

importance of

‘craftsmanship’ – the umbilical cord binding art to genre – which was only further emphasized by phenomena such as pop art, where objects

and imagery from a lowbrow popular culture could be recast in a completely new

context. The acme of this

‘trans-generic’ shift within the visual arts was perhaps the appearance of installations: the

anti-genre par excellence. The installation can amorphously incorporate an

unlimited variety of material; it lends itself in a protean fashion to whatever

aim the artist may have.

We are today living in a world where the genre system has lost its normative

grip over aesthetics. But that does not necessarily mean that genres have

disappeared entirely. During the sixties some critics, such as Clement

Greenberg and Michael Fried, feared that the challenge to the laws of genre

would ultimately lead to the disappearance of art as such. That has not been

the case. Art is still there, and genres still have their meaning

– but now as an aesthetic tool or a practice on par with all the others. What is

demanded today from artists working in the fields of sculpture, painting,

drawing and so on,. is a sensibility unbeknown to earlier generations of

colleagues. It is a sensibility that must be aware of recent developments in

order to generate meaningful works of art. Works that can be technically

brilliant without collapsing into academicism, confer an idea without yielding

to an oblique imagery or cheap bombast, and last, but not least, partake in a

contemporary aesthetic dialogue without becoming trapped in an ideological

cul-de-sac.

This is what the eight artists present at the show have in common. There is no

other external factor that binds them together. They represent different

nationalities, genders, generations and practices. What they share is a

contemporary approach to genres: intelligent, innovative and thought-provoking.

With different attitudes vis-

à-vis concepts, materials and techniques they show us which aesthetic strategies,

relative to genres, it is possible to uphold in today

’s complex and ever-changing visual landscape.

Take the German artist Stephan Balkenhol as an example. His Untitled suggests a relation to a Northern European tradition of woodcarving that goes

back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. But at the same time his works are

devoid of any reference to a classical ideal of beauty or those heroic poses

that are so well known to us from the history of monumental sculpture.

Balkenhol

’s aim is rather to find a position of ‘extreme neutrality’ – emphasized by the everyday qualities and dead pan expression of his figures.

His works could perhaps be seen as

‘odes to the common man’, where unremarkable and nondescript individuals are placed on the type of

pedestal normally reserved for kings and warriors, but for the fact that every

form of symbolic or allegorical reading has been thoroughly exorcised from his

art.

In Balkenhol’s sculptures we see the workings of chisel and hammer. The method of sculpting

figures, leaving the untreated wood as a sort of base, makes his art forever

bound to its material context. It is a way to be honest towards the viewer: by

revealing the tools and processes by which a work of art is made, he succeeds

in liberating a genre from an all too charged tradition, and gives it a new and

absolutely original direction.

In the field of painting, the Californian artist Kristin Calabrese represents

another strategy. She works in a large, overwhelming format and with a distinct

imagery, where political, as well as emotionally charged themes seem to work

together without generating contradictions. In her monumental canvas

The Price of Oil (2004), we see young men and women piling up, as if framing the big void visible

in the middle. But what do we actually see here? Is this a throwback to

political art of the sixties? Do the human bodies, stacked like objects on a

shelf, represent the commodification of men and women within an oil-dependent

capitalist society? If this was the only thing this work had to convey, it

could certainly be described as a nostalgic echo. But, with wit and

playfulness, Calabrese formalizes concrete imagery from mundane, everyday life

in an abstract fashion, in order to make a comment on painting as such. The

price of oil does not necessarily refer to global capitalism, but rather to the

costs of upholding a genre so often declared dead, but still very much alive

and kicking.

German artist Torben Giehler belongs to a new generation of artists who fuse

different techniques, such as digital media and traditional painting. His works

often start as freehand drawings in colour that are digitally photographed and

downloaded into a computer. Using Adobe Photoshop software, he breaks down the

images and reassembles them into models for acrylic paintings, often executed

in a large format.

We are surrounded by digital imagery. We see it in movies and video games. The

military, corporations and scientists make use of it, and ordinary citizens

rely on it at home and at work. Information technology has also made us more

aware of how images are generated and of the possibility of altering a visual

object. In today

’s world, no one would ever dream of saying ‘the camera never lies’. But this visual explosion has until now had rather meagre effects when it

comes to the visual arts. Computer generated imagery has been blocked by an

urge to imitate

‘reality’. Fantastic constructions of imagined pasts or futures, lead to an obsessive

focus on realism and faithfully reproduced objects. In this perspective Giehler

’s abstract landscapes are a proof that digital media has finally matured.

Giehler

’s exuberant colours and expansive quasi-geometric forms project an environment

that is truly virtual. The viewer will identify certain parameters such as

mathematical composition principles, and a rhythmic

– almost architectural – proportionality of lines and surfaces that is further emphasized by the dynamic

use of colour. In his works he succeeds in generating a world that intertwines

and transcends physical nature, technology, and our own innermost psychological

mindscapes.

The British sculptor Antony Gormley has worked with the human body as his

artistic point of departure for many years. The emphasis has often been on the

intricate relationship between the

existential experience of having a body on one hand, and the phenomenological experience of a body occupying a certain physical space on the other. In spite

of the prominent role played by the human body within the history of art, it is

rather the philosophical implications that are featured in his sculptures. True

to this aim, his main object has always been his own body. Many of his earlier

works are characterized by representations of fundamental physical properties,

such as the extension and location of a body in space. Since certain primordial

categories, such as up and down, front and back, are necessary for our

experience of spatial qualities, he often places his works in unexpected

positions, such as hanging from the ceiling or mounted on the wall, as if

defying the forces of nature, as well as our mental capacity to understand.

In recent years Gormley has somewhat broadened his aesthetic scope. Many of his

latest works do not focus on the phenomenological, so much as the perceptual

aspects of the body. The question is not how a body

‘places itself’ in an outer physical space, but rather in the inner space of the viewer. His Sublimate II (2004) is instructive in that regard. The body has been broken up,

deconstructed into a system of rectilinear solid steel blocks in various sizes.

What we see is a representation where the viewer has to recompose the shape in

his own mind in order to make it appear as an image. There are obvious

parallels to how a computer breaks down an image into pixels, or even to

Gestaltenpsychologie, but Gormley’s sculptures have wider implications. His works do not merely require analysis

in the gaze of the beholder; they also reveal what qualities are demanded of an

object in order for it to appear as a work of art.

The American artist Peter Halley has for many years painted abstract works that

can be seen as inspired by the angular and strict geometry of Benthamian prison

cells or modern-day computer chips. His paintings have a direct and striking

visual impact on the viewer through their scale, colour and relentless

consistency. Even if it is tempting to place Halley in a tradition represented

by Mondrian and Newman, one must keep in mind that his works are not simply

‘abstractions’, since geometry in itself is seen as a metaphor for society. Cell units, linked

by linear trajectories, represent the rhythm of contemporary social existence

and the workings of the capitalist economy

– constantly swinging between isolation and hyperconnectivity; urban alienation

and high-octane activity.

His two works, Collacation (2004) and Six Prisons in Color (2004) are in this respect vintage Halley, where simple diagrammatic structures

can be seen as a way to dramatize a political and social arena dominated by

media, technology and consumer culture. Both minimalism and pop art have served

as important and clearly visible sources of inspiration in Halley

’s work, but he has nothing of the former’s dogmatic tendencies nor the latter’s weakness for overemphasizing the iconography of contemporary culture. Halley

works in a non-programmatic and often intuitive way that injects his art with

vitality and a surprising emotional streak.

VIK MUNIZ.

DON QUIZXOTEIN HIS STUDY (detail), AFTER WILLIAM LAKE PRINCE.

2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

232.5x193 cm.

DON QUIZXOTEIN HIS STUDY (detail), AFTER WILLIAM LAKE PRINCE.

2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

232.5x193 cm.

Tony Matelli, another American artist, creates hand-painted hyperrealist

sculptures from silicone, resins and human hair that often are as hilariously

funny as they are deeply worrying. To enter an exhibition by Matelli is to

enter a world where the codes that regulate our normal social behaviour have

been suspended, and where new and unknown rules have been brought into play.

His works appear as if from a dream, where desires, fears and unrelated

appearances collude in a sometimes horrifying, sometimes liberating sense of

incomprehensibility.

Ideal Woman (1998–99) embodies an ambitious risk – socially, emotionally, intellectually and aesthetically. Reclaiming a cartoon

half-remembered from an old Hustler, which crudely sketched the

‘perfect woman’ as a self-service sex machine, the piece revels in comedic grotesquery. The

ideal imagined by this particular macho reduction, rendered uncomfortably

‘real’ in three dimensions, is four foot tall and flat-headed. Naked but for black

panties, she stands on a square of cheap carpet amid empty beer bottles and

cigarette butts. Her toothless smile curves serenely toward meaningfully

oversized ears.

Cast in silicone rubber, the figure’s freckled skin has a touchable fleshiness. Its opalescent green eyes, framed by fine lashes and brows, shine with lifelike appeal. The piece is enlivened by rasping contradiction: delicate craftsmanship (and the kind of attention to detail one could only describe as loving), jars against the crude affront of the image it realizes. A subtle contrapposto, at odds with the awkward distortion of lumpen proportions, resonates directly against classical idealizations of the nude female form. Yet, beckoning warmly, arms outstretched in a gesture that subtly invokes religious iconography, the figure is imbued with grace. ‘Disturbing and inscrutable, simultaneously compelling and repellent, it is profoundly eerie to be around ’ (Fischman).

In Fuck’d (2004) we meet a chimpanzee in distress. A dismembered monkey is seen stumbling

across the gallery floor, pierced by a multitude of tools and weapons dating

from every epoch of history. The apparent allusion goes to Kubrick

’s film 2001 – A Space Odyssey (1969), where a pre-historic monkey discovers the first tool. By using a bone

from a dead animal as a weapon, and by taking control over his troop, he

unconsciously invents civilization. In Fuck

’d civilization has turned against its own inventor. In Matelli’s personal and subjective universe there is always room for unintended

consequences, but also for a generous understanding of the bewildering

condition of being human. He once said about his figures:

‘They are bewildered because I am bewildered. I feel this is a contemporary state

of being.

’

VIK MUNIZ.

NASTURTIUMS. AFTER FANTIN LATOUR (still lifes).

2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

287x193 cm.

NASTURTIUMS. AFTER FANTIN LATOUR (still lifes).

2004.

Framed chromogenic print mounted on aluminum,

287x193 cm.

Vik Muniz began as a sculptor in his native Sao Paolo, Brazil, but gradually

became interested in photography. A central feature in his works is an interest

in art history, which surfaces throughout his production. Muniz has also become

famous for a certain kind of

‘material promiscuity’. As a preparation for his photographs, he creates sculptures or paintings in

materials as diverse as chocolate, sugar, dirt, dust, or cotton. These

‘low-tech illusions’, as he calls them, are then photographed and often destroyed afterwards. His

method of composition is apparent in

Don Quixote in His Study, After William Lake Price (2004), based on one of the illustrations to the English edition of Cervantes’ literary masterpiece. When closer scrutinized, the photograph reveals its

constituent parts of heterogeneous objects. Here Muniz excels in what has

become something of his trademark: A capacity to distort, as well as sharpen

the viewer

’s perception of an image.

Muniz belongs to a generation of artists who have pushed the conceptual

tradition a step further. The visual icons of today do not exclusively belong

to religion or art, but may originate in a context of commercial or political

marketing as well

– as is obvious in Muniz’s Rosie, the Riveter (2004), based on the famous US propaganda poster from the Second World War

(whose aim was to urge women to take up positions in heavy industry). With his

combination of humor and critical approach, iconolatry and iconoclasm, Muniz

challenges aesthetic convention, good taste, and highbrow culture; as in his

two

‘still lifes’, Nasturtiums, after Fantin Latour (2004) and Water Lilies, after Monet (2004), where he proves that a work of art is as much an element in a cultural

code of communication as an object for aesthetic contemplation.

One of Tony Oursler’s aims has been to penetrate the impact of contemporary television culture upon

the modern-day psyche. In many of his video works he presents us with

characters that seem to be forever trapped in a semi-parasitic/semi-symbiotic

relationship with technology, and whose last line of defence, in order to

retain at least one bit of authentic subjectivity, appears to be a retreat into

a psychotic state of mind. Oursler has a large and varied production, where the

depth of his conception is thoroughly matched by technical brilliance. His

works cover a wide range of expressions, from intimate video sculptures to

expansive site-specific installations. His work expresses a

‘trans-generic’

modus operandi, where sculpture, video and performance elements blend into one another.

In a work such as Star (2003) we find surprising attributes of classical

sculpture, although realized in a truly innovative fashion. During the last

hundred years, sculpture has gradually drifted away from its monumental origin.

Overt allegorical and narrative elements have disappeared together with the

plinth. A war memorial today would hardly display heraldic emblems and heroic

warriors cast in bronze. It would rather use as unsymbolical means of

expression as possible, perhaps borrowed from minimalism. Oursler breaks free

from this modern-day

‘muteness’ by challenging aesthetic conventions and stylistic dicta. Through the use of

technology, such as video projections on volumes, he reinvents plasticity and

reconquers the function of narrative on behalf of sculpture; and by injecting

an element of performance he admits the genre to be evermore itself and fulfill

its inherent potentialities.

*The materials are presented by Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Inc. (Moscow branch).

www.tatintsian.com