Topics: Economics / Politics

01.02.2004

Russia must analyse the challenges facing developed nations not for a blind

replication of Western solutions but for carefully adjusting Western

experiences to Russian specifics and ensuring that a possible problem is

addressed before it entrenches and a needed reform is overdue.

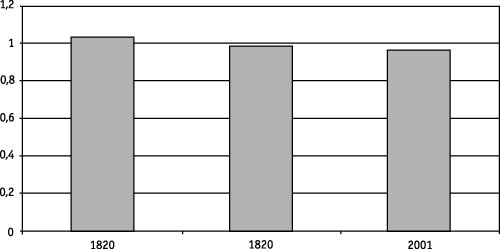

In discussing Russia's long-term prospects, it is important to analyse how the

country has been developing over

the last two centuries, rather than over three or ten years. If we consider the

evolution of Russia's economy against the background of global development over

the last two centuries, we discover that in 1820 Russia's GDP per head was

close to the average worldwide indicators and it remained roughly on the same

average worldwide level (taking into account the accuracy of the calculations)

both in 1913 and 2001 (see Fig.1).

Fig.1. Correlation between Russia's GDP per head and the world GDP per head from 1820 to 2001

Source:

1. For 1820 and 1913: A. Maddison. The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective.

2. For 2001 – the IET computations based on the data of A. Maddison.

3. Reconstruction of World Bank data pre 1950 provides similar results within the limits of accuracy of calculations.

1. For 1820 and 1913: A. Maddison. The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective.

2. For 2001 – the IET computations based on the data of A. Maddison.

3. Reconstruction of World Bank data pre 1950 provides similar results within the limits of accuracy of calculations.

It is fairly easy to explain the reasons for the selection of these particular

dates. Most researchers believe that modern economic growth

– a process of drastic acceleration in the pace of economic development

accompanied by large-scale shifts in the structure of the economy and social

relations

– started in the 1820s[1]; 1913 – is the peak of the Russian Empire's development, while 2001 is the most recent

date for which data is currently available.

Naturally, Russia's GDP was deviating from the World, average between these

three points, but such fluctuations were fairly moderate. The gap between

Russia and the leading nations in world development (the UK in the 19th Century

and the US in the 20th Century) has been fluctuating over these two centuries

too, but again these happened within rather a narrow range (see Table 1).

Table 1. Correlation between Russia's GDP per head and GDP per head of the

leading nations in modern economic growth*

| Year | 1820 | 1870 | 1913 | 1950 | 2001 |

| Ratio | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

* 1820-1870 – UK, 1913-2001 – US

Over the last quarter of the 20th Century, it has been China's successful record

of economic performance that has drawn everyone's attention. Ironically the

fact that a drastic fall in China's share in the world economy has constituted

one of the most profound structural shifts in the latter between 1820 and the

1970s is often ignored. Nowadays, after some 25 years of rapid growth, the

country's share in the world GDP is a third of its equivalent in 1820, while

its

GDP per head currently accounts for roughly half of the average global level

(while in 1820 it was on a par with it).

Against such a background, the closeness of Russia's economic indicators to

their respective global averages is worth the attention, and it becomes even

more important considering that world economic development has undergone

unprecedented changes over the last two centuries.

It was an outstanding US economist S. Kuznets who introduced the concept of

modern economic growth in economics. He believed the phenomenon emerged in the

late 18th Century[2]. Today, this view is being challenged by some of the most

authoritative experts who are more inclined to date it back to the 1820s

– the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars.

The exact date is of no fundamental significance – what matters is the sharp acceleration of growth rates of the world economy and

GDP per head between the late 18th and the early 19th Centuries that was taking

place against the background of radical structural transformations in

employment, geographical expansion, and demography.

Prior to the modern economic growth era it took Western Europe, the region that

had been developing abnormally fast over the previous millennium, eight

centuries (roughly between 1000 to 1800) to double its GDP per head during the

period. The leader of modern economic growth in the 20th Century the US, has

seen its productivity rising on average by 2 %, that is 2% for over the last

two centuries. It means that during a single generation's lifetime (75 years)

per head GDP has grown more than 4-fold.

A number of common sweeping mutually related transformations have been taking

place in countries with seemingly different cultural traditions, resource

bases, and geographical locations. It would only be logical to assume that an

understanding of these general processes which follow similar scenarios related

to economic development would provide a strong tool to a researcher dealing

with long-term economic growth.

It is no coincidence that faith in the ability of such absolute laws of

historical development to predict and logically explain the world formed the

core of Marxism, a theory which between the late 19th

– early 20th Century dominated the study of the long-term prospects for the

evolution of socio-economic relations. Yet the 20th Century has also exposed an

important feature of modern economic growth that neither Marx, nor Marxists had

been able to product in their time: modern economic growth is accompanied by

rapid and unpredictable changes in the dominating trends in socio-economic

systems and nation

’s economies. The history of socio-economic theory over the last two centuries is

rife with dramatic errors of great thinkers who attempted to extrapolate the

trends they had witnessed in their time onto the future. Notably among them

were T. Malthus, with his prophecy of overpopulation and global starvation

which he based on the actual facts he had witnessed in his lifetime, such as a

rise in life expectancy and lower infant mortality

– all of which we now know were attributes of an early stage of demographic

transition; Karl Marx, with his prognosis of an absolute and relative

impoverishment of the proletariat, social destabilization and the collapse of

capitalism, which he in his turn based on actual social problems of the early

stages of modern economic growth; J. Shumpeter, who in his book entitled

Сapitalism, Socialism and Democracy forecasted the fading of entrepreneurship

and the bureaucratisation of economic life, no doubt a product of the grim

reality of assembly line manufacturing dominant in his time.

In financial and fiscal theory, the concept of the impossibility of exceeding

the then existing upper marginal taxation rates has been a convention until the

late 19th Century. In the 1870s A. Wagner questioned that paradigm and was the

first to formulate a hypothesis stating that the share of resources subject to

the government's re-allocation would rise in parallel with the size of the

economy. The hypothesis found its empirical proof in the 20th Century, when a

drastic expansion of the modern states' capacity against a background of rising

living standards, allowed considerable increases in state withdrawals from the

GDP. From 1910 and 1970, the idea of unlimited horizons for increasing state

tax revenues became an accepted view in financial literature, while

researchers, who tried to argue that even in industrial economies there is a

limit to state taxation compatible with economic growth, were ridiculed.

In the 1970s this conventional view came under scrutiny as the evidence grew

that in developed nations, where taxation rates hit levels close to 50% of the

GDP, they were plagued by serious problems such as politically organized

taxpayers' resistance and expansion of the shadow economy, a slowdown of

economic growth and a loss of competitiveness on the international markets.

From the current perspective, it is evident that the process of tax withdrawals

rising from the levels characteristic of agrarian societies (some 10% of the

GDP) to the one available for highly developed post-industrial economies

(30-50% of the GDP) was transitional. It was practically impossible to forecast

its development until it was over.

Whilst advocating the gold standard in the UK at the end of World War 1 and

pursuing a deflationary policy for the sake of re-establishing the British

Pound's parity with gold, Winston Churchill was guided by a two-century-long

national tradition that had ensured the United Kingdom's role as the world

economic leader. Churchill essentially repeated what had been done in the

aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, yet, given the radically changed conditions,

such a policy was encouraging the world towards one of the most intense

economic crises of the past century

– the Great Depression. The gold standard that had played a crucial part in

launching modern economic growth later proved to be incompatible with the

consequent stages of growth.

The fact that modern economic growth appears an incomplete, ongoing process, of

which rapid and radical changes in dominating trends are characteristic,

substantially complicates the use of exposed regularities to forecast the

development of the leading countries that form a vanguard of mankind's economic

development. But the leading nations, i.e. those that began their economic

growth in the first decades of the 19th Century hold a different position than

those who underwent modern economic growth and the respective socio-economic

transformations somewhat later[3]. The experiences of the pioneering group

allow important conclusions to be drawn on challenges and trends that will face

the latter group, i.e. the so-called catch-up development nations, in the

future.

Leading nations and catch-up economies

There are authors that assume the inevitability of a further development in the

globalization process, and those who believe that the world is on the threshold

of de-globalization. It is impossible to prove either assumption, but one can

argue, with a high level of probability, that over the next 50 years, Russia

will have to cope with the problems that leading nations in modern economic

growth were tackling during the second half of the 20th Century, at the stage

now called post-industrial.

One of the greatest economists in the world history, Adam Smith avoided numerous

mistakes characteristic of his followers precisely because he analyzed problems

related to catch-up development[4]. He was not concerned about the problems and

prospects of Holland

– then a European economic leader, for he believed that the country had reached

the level of its maximum possible productivity and would from then on slide

into stagnation[5].

Karl Marx has extended the concept that the current state of the more developed

nations was a preview of a future for their less developed peers into a stern

determinism. He argued that,

”It is not the high or low level of development of those social antagonisms which

proceed from the natural laws of capitalist production. It is the laws and

tendencies themselves that function and realize themselves with a strict

necessity. A more industrially developed country shows a less developed one but

a picture of its own future

”[6]. However, Marx underestimated three important factors that separated the

paths taken by catch-up development nations from

leading nations, development trajectories of which have already manifested

themselves in the 20th Century.

The first of them is the sustaining gap between leading nations and catch-up

development nations. The dissemination of knowledge and technologies born by

modern economic growth appears unevenly dispersed: for instance, a mass

application of modern anti-epidemiological means in catch-up development

nations occurs at a far greater pace than the spread of modern business

technologies. The fall in the mortality rate and the rise in the life

expectancy now takes place during earlier stages of economic development. Since

in today's poor countries the lower mortality is also combined with a high

birth rate, their share in the world populations is rising

The second factor is the importance of the conditions of the global economic

environment set by its leaders. The latter undergo different stages in their

structural transformations that impact the whole world economy. More

specifically, between the 1870s through to the 1910s the world economy had been

functioning in the conditions of a global commodity and capital market based on

the gold standard. That influenced the economic strategy options of the nations

that entered the process of modern economic development during those decades.

Between 1914 and 1950 the global development found itself severly affected by

wars, the crisis of the gold standard, and a protectionist policy that pre-set

the limits for maneuver values for the catch-up development nations, thus

forcing them towards opting for a protectionist policy and import-substitution

industrialisation. In the late 20th Century, the world once again entered the

era of globalization marked by lowered customs tariff rates and the opening

capital markets

– all taking place under floating rates of major world currencies: rather than

the gold standard. That created new opportunities favoring strategies aligned

towards boosting exports and integration into the world economy.

Regretfully, however hard we try, in the coming decades the world development

context will be set by developments advanced by the US, Western Europe and

Japan, rather than Russia, India, or Brazil. The economic and political

processes that manifest themselves in the leading nations will have a strong

effect on the national development strategies of nations following in their

footsteps.

The third factor that determines the specificity of the catch-up development

path is various national traditions inherited from the respective agrarian

civilizations. For instance, the family relations which emerged in Western

Europe over the last millennium appear different from those in Muslim

countries, as well as those dominated by Buddhism or Confucianism. The spread

of a small or big family and family solidarity customs exercise a substantial

impact on the development of social protection systems, national savings

standards, and economic development as a whole.

The significance of the leading countries' experiences for catch-up development

nations lies with the appreciation of the strategic challenges that they will

face, a way of minimising risks and avoiding a predecessor's mistakes, rather

than blindly copying them.

Had Marxism been as popular in today's Russia as it was in the early 20th

Century, the context and key terms of the debate on the national long-term

development problems would be as follows the trends of transformations of

socio-economic establishments in the leading countries in of economic growth;

the ability of Russian national institutions to adapt accordingly; the measures

that would allow the adjustment of Russian establishments to relevant

challenges in economic development[7].

The collapse of the socialist experiment has seriously undermined the popularity

of Marxism in the country. But as the saying goes,

”do not throw the baby out with the bathwater.” In other words, the experiences of the most advanced nations' socio-economic

development over the last half-century has some valuable lessons for

understanding the challenges Russia will face in the first half of the 21st

Century.

If one compares Russia's current GDP per head with that of the leading nations

in economic growth one will be able to fully appreciate the gap that exists

between them (see Table 2).

Table 2. The years when GDP per head of the leading nations in modern economic

growth was equal to Russia's

| Country | Year |

| USA | 1935 |

| Australia | 1936 |

| Canada | 1941 |

| New Zealand | 1948 |

| UK | 1934 |

| Sweden | 1944 |

| Germany | 1953 |

| France | 1951 |

| Italy | 1959 |

Source:-

1. Russia's GDP per head – data from the World Development Report, World Bank, 2003, in USD equivalent- Geary-Khamis, 1990.

2. The data on GDP per head in other countries, see: A.Maddison. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992, OECD 1995.

1. Russia's GDP per head – data from the World Development Report, World Bank, 2003, in USD equivalent- Geary-Khamis, 1990.

2. The data on GDP per head in other countries, see: A.Maddison. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992, OECD 1995.

The accuracy of the calculations of GDP per head in purchasing power parity

(PPP) terms appears rather limited, so one should exercise caution while

drawing conclusions from such comparisons. But the data presented in Table 2 on

the whole show that the gap between Russia and leading nations today amounts to

about 40 to 60 years.

Let us compare the evolution of Russia's GDP over a long period with those of

the large countries of continental Europe (France and Germany). While

considering the distance between Russia and the leading countries, it is

worthwhile to take these particular countries as a starting point: like Russia,

they were involved in two World Wars on their territories in the 20th Century

which had a similar distorting effect on their development

Table 3. Russia's backwardness in contrast to Germany and France in terms of

GDP* per head (in years)

| Countries | Years |

|||

1870 |

1913 |

1950 |

2001 |

|

| France | 60 |

63 |

46 |

50 |

| Germany | 60 |

63 |

55 |

48 |

*Russia's GDP per head until 1913 implies the Russian Empire within the USR

borders, in 1950

– the USSR, in 2001 – the Russian Federation

Source:

1. The data on GDP per head 1870-1950, see: A. Maddison. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. Development Center Studies, OECD, 1995.

2. The data on GDP per head in 2001 – see: the World Development Report 2003. The World Bank. The data in USD equivalent – Geary-Khamis 1990.

Source:

1. The data on GDP per head 1870-1950, see: A. Maddison. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. Development Center Studies, OECD, 1995.

2. The data on GDP per head in 2001 – see: the World Development Report 2003. The World Bank. The data in USD equivalent – Geary-Khamis 1990.

The data presented in Table 3 shows that Russia's backwardness compared to

Germany and France in terms of GDP per head has been fairly stable over one and

a half centuries[8].

This is not random, out-of-context data on the GDP per head of Russia, France,

and Germany

– the noted changes generated other significant structural transformations in

these particular economies.

Table 4. The proportion of urban population in the overall population of

Germany, France and Russia, at 50 year intervals (%).

| Countries | Years |

|||

| 1850 – Russia 1800 – Germany, France |

1910 – Russia 1850 – Germany, France |

1950 – Russia 1910 – Germany, France |

2000 – Russia 1950 – Germany, France |

|

| Russia | 7 | 14 | 44,7 | 77,7 |

| Germany | 9 | 15 | 49 | 71,9 |

| France | 12 | 19 | 38 | 56,2 |

Source:

1. 1800-1900: P.Bairoch, Cities and Economic Development: from the Dawn of History to the Present, Chicago, 1988

2. 1950-2000: The UN database (http://esa.un.org/unpp)

Table 4 contains data concerning the dynamics of the share of Russia's urban population in Russia, Germany and France over the last two centuries at 50 year intervals and shows a similar picture, i.e. Russia's backwardness roughly amounts to two generations (150 years).

1. 1800-1900: P.Bairoch, Cities and Economic Development: from the Dawn of History to the Present, Chicago, 1988

2. 1950-2000: The UN database (http://esa.un.org/unpp)

Table 4 contains data concerning the dynamics of the share of Russia's urban population in Russia, Germany and France over the last two centuries at 50 year intervals and shows a similar picture, i.e. Russia's backwardness roughly amounts to two generations (150 years).

Table 5. The share of employed in the agrarian sector out of the total

economically active population of Germany, France and Russia, at 50 year

intervals (%)

| Countries | Years |

||

| 1900 – Russia 1850 – Germany, France |

1950 – Russia 1900 – Germany, France |

2001 – Russia 1950 – Germany, France |

|

| Russia | 59.11 (1897)(*) | 45.83 (1959) | 10.02(3) |

| Germany | - | 36.84 (1907) | 23.63(2) |

| France | 51.72 (1856) | 41.43 (1901) | 24.06(2) |

* Here and throughout the Table after some of the figures there is a date in

pocken thesis. The date is the closest to the one required, given the avialable

date.

Source:

1. (If not stated otherwise) B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998

2. Groningen Growth&Development Center Sectoral database (http://www.eco.rug.nl/ggdc)

3 Rossiisky statistichesky ezhegodnik, Goskomstat Rossii, 2002.

Source:

1. (If not stated otherwise) B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998

2. Groningen Growth&Development Center Sectoral database (http://www.eco.rug.nl/ggdc)

3 Rossiisky statistichesky ezhegodnik, Goskomstat Rossii, 2002.

Table 6. The share of employed in the industrial sector out of the total

economically active population of Germany, France and Russia, at 50 year

intervals (%)

| Countries | Years |

||

| 1900 – Russia 1850 – Germany, France |

1950 – Russia 1900 – Germany, France |

2001 – Russia 1950 – Germany, France |

|

| Russia | 13.87 (1897)(*) | 40.27 (1959) | 24.97(3) |

| Germany | - | 33.84 (1907) | 35.21(2) |

| France | 23.30 (1856) | 26.53 (1901) | 26.82(2) |

* Here and throughout the Table after some of the figures there is a date in

pocken thesis. The date is the closest to the one required, given the avialable

date.

Source:

1. (If not stated otherwise): B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998

2. Rossiisky statistichesky ezhegodnik, Goskomstat Rossii, 2002.

3. Groningen Growth&Development Center Sectoral database (http://www.eco.rug.nl/ggdc)

Source:

1. (If not stated otherwise): B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998

2. Rossiisky statistichesky ezhegodnik, Goskomstat Rossii, 2002.

3. Groningen Growth&Development Center Sectoral database (http://www.eco.rug.nl/ggdc)

Tables 5 and 6 illustrate similar structural changes in employment; notably, a

faster contraction in employment in Russia's agrarian sector is most likely to

be associated with specific features of the socialist industrialization model.

In the USSR, a large-scale reallocation of resources from the agrarian sector

to finance investment in the industrial sector created strong incentives for an

exodus of peasants from the countryside.

We consider the countries' development paths over the period of one and half

centuries that cover the stage of drastic socio-economic transformations. In

Russia, this particular period comprised of two revolutions, the collapse of

two empires, two World Wars and one Civil War, the greatest socio-economic

experiment in world history called socialism, and its break-up. Nevertheless,

during the period in question the gap between Russia's level of development and

that of the largest nations of continental Europe remained fairly stable and

roughly amounted to two generations (50 years). Having started modern economic

growth as early as two generations after Western Europe, i.e. in the 1880s,

Russia has maintained that gap. This, by no means should point us to a

conclusion that such a time lag is somehow pre-destined to remain forever.

Nonetheless, a careful analysis of the development of the socio-economic

processes in the leading nations of economic growth in the last five decades

clearly proves to be a useful tool estimating Russia's long-term prospects.

W. Easterley demonstrated the vulnerability of existing models that attempt to

explain the differences in national economies' growth rates[9]. He showed that

for each factor, believed to be the single most important determinant of

growth, (be that the share of investment in GDP, educational expenditure,

etc.), there will always be a number of countries which satisfy that criteria

yet do not exhibit growth. With that hypothesis Easterley also introduced an

imprecise, but an interesting term

– ”national institutions' capacity to secure economic growth”. Should we apply this concept to the realities of Russia's development over the

last one and a half centuries, it can be argued that Russia's socio-economic

institutions' capacity to secure economic growth has been at the average

worldwide level over the entire period in question.

If we agree with the hypothesis that the gap which remained for over one and a

half centuries will continue, then in 50 years time Russia's living standards,

lifestyle, employment structure, and infrastructure will be roughly the same as

those currently noted in Germany or France. That suggests an annual growth rate

in GDP per head of some 2%, i.e. the pace of growth in the world economy over

the past five decades. Should the Russian economy be developing at the present

pace, i.e. by some 4% annually, over the forthcoming decades, this gap could be

partly bridged in 25 years, thus allowing a reduction in its backwardness from

the leaders down to one generation.

The awareness of the scale of the gap that has long separated Russia from the

leading nations is necessary not for the sake of manipulation with the figures

of growth and the creation of forecasts on their basis. Rather, it is

necessary, first, to form a clear vision of where the difference between

Russia's past development from that of leading nations lay and apparently

remain; and second, what structural challenges will the country face in future

stages of its economic development.

Russia's demographic dynamics: the specific legacy of socialism

As far as a set of key socio-economic characteristics is concerned, the area

where Russia's development appears different from that of leading nations is

its demographic dynamics (see Table 7)

Table 7. The share of nations in the world population (%)

| Countries | Years |

|||

| 1900(2) | 1950 | 2000 | 2050 | |

| Russia | 4.31(4) | 4.03 | 2.34 | 1.04 |

| US | 4.63 | 6.26 | 4.55 | 3.96 |

| Japan | 2.67 | 3.32 | 2.04 | 1.09 |

| UK | 2.33 | 2.01 | 0.95 | 0.59 |

| France | 2.46 | 1.66 | 0.95 | 0.62 |

| China | 24.24 | 22.01 | 20.47 | 14.59 |

Source:

1. (If not stated otherwise) Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the UN Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2001 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpp (moderate projections for 2050).

2. A.Maddison. Development Center Studies. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. OECD, Paris, 1995.

3. The ratio of Russia's population in 1897 (according to Source 4) to the world population in 1900 (according to source 2) ratio

4. Naselenie Rossii za 100 let (1897-1997), Goskomstat Rossii, M., 1998.

1. (If not stated otherwise) Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the UN Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2001 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpp (moderate projections for 2050).

2. A.Maddison. Development Center Studies. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. OECD, Paris, 1995.

3. The ratio of Russia's population in 1897 (according to Source 4) to the world population in 1900 (according to source 2) ratio

4. Naselenie Rossii za 100 let (1897-1997), Goskomstat Rossii, M., 1998.

The decline in Russia's share of population in the overall global population

does not constitute a unique phenomenon. The non-immigrant leading nations have

also experienced a steady decline in their respective shares over the last

century. The difference in this respect lies with the fact that Russia, which

started its modern economic growth two generations later compared to the

leaders and had its share in the world population rapidly increasing in the

early 20th Century, was supposed to, providing an inertial development of the

situation, have by the late 20th Century a far greater proportional number than

it actually has now.

What happened in Russia was related both to large-scale social catastrophes (two

world wars, the civil war, collectivization, repressions) and the specifics of

the socialist industrialization model the country pursued for the most part of

the last century.

Table 8. The share of women in the total number of the economically active

population (%)

| Country | Years |

||

| 1900(1) | 1950(2) | 2000(2) | |

| Germany | 30.7(1907)* | 38.9 | 42.3 |

| Russia | 16.4(1897) | 51.5 | 49.2 |

| France | 35.3(1901) | 31.8 | 45.1 |

* Here and throughout the table the year on which the respective index (the

closest to the required year out of the data available) is given in

parenthesis.

Source:

1. Calculated basing on: B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998.

2. Calculated based on the data of the United Nations Common Database, Economically active population by sex, 13 age groups (ILO estimates/projections).

Source:

1. Calculated basing on: B.R.Mitchell, International Historical Statistics 1750-1993, Macmillan Reference LTD, 1998.

2. Calculated based on the data of the United Nations Common Database, Economically active population by sex, 13 age groups (ILO estimates/projections).

The data presented in Table 8 shows that the socialist model of

industrialisation suggested an unusually early involvement of women in

employment outside the household. As early as 1950 the women's share in the

overall number of employees in Russia had already been greater than it would

have been in France and Germany by 2000, i.e. at the stage of a developed

post-industrial society. The process of getting women involved in employment

entails a parallel process of contraction in the number of births per woman.

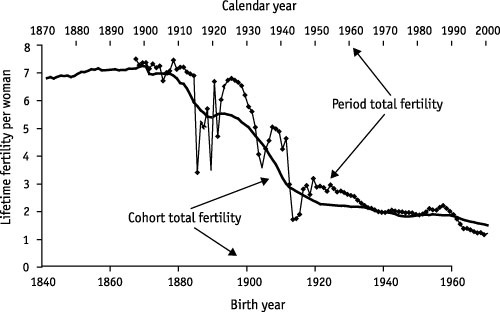

The data of Table 9 shows the development of this particular process in Russia,

Germany, France, and Spain[10]. From the perspective of demographic processes

associated with modern economic growth, Russia had begun to witness the fall in

the average lifetime fertility per woman roughly in two generations earlier

than the leading nations.

Table 9. The average lifetime fertility per woman

| Country | Years |

||

| 1950-55 | 1975-80 | 1995-2000 | |

| Germany | 2,16 | 1,52 | 1,34 |

| Spain | 2,57 | 2,57 | 1,19 |

| Russia | 2,85 | 1,94 | 1,25 |

| France | 2,73 | 1,86 | 1,76 |

Source: the UN database (http://esa.un.org/unpp)

The statistics of births is distorted by the impact of demographic waves caused

by the two World Wars. The data arranged by S. Zakharov concerning the lifetime

fertility rate per woman in Russia across the total age cohorts and presented

below in Fig.2 is built on their basis and show a correlation between the path

of demographic transition and the socialist model of industrialisation.

Fig. 2

Source:

Zakharov S.V. ”Rozhdayemost v Rossii: pervy i vtoroy demographichesky perekhod”/”Demographicheskaya modernizatsia, chastnaya zhizn i identichnost v Rossii”, abstracts of presentations of a scientific conference, Moscow 27-28 February 2002. M., TSDECH RAN, 2002, pp. 19-26. These materials are available courtesy of S.V. Zakharov.

Zakharov S.V. ”Rozhdayemost v Rossii: pervy i vtoroy demographichesky perekhod”/”Demographicheskaya modernizatsia, chastnaya zhizn i identichnost v Rossii”, abstracts of presentations of a scientific conference, Moscow 27-28 February 2002. M., TSDECH RAN, 2002, pp. 19-26. These materials are available courtesy of S.V. Zakharov.

Yet another factor that determined the decline in Russia's proportion in the

overall global population is also associated with the socialist

industrialisation model. As the data presented in Table 10 shows, one can see a

gradual convergence between Russia's life expectancy indices and those of

leading nations in economic growth until the mid-1960s, while the process has

discontinued hence[11]. The sustainability of Russia's life expectancy figures

against a background of the growing gap between the nation and the leading

nations over nearly

40 years has constituted a very unusual fact in the world demographic history.

Table 10. The average life expectancy rates at birth (as years)

| Country | Years |

|||||

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | |

| Russia | 64.5 | 67.9 | 69.7 | 68.3 | 66.9 | 66.1 |

| USA | 68.9 | 70.0 | 71.5 | 74.0 | 74.9 | 76.2 |

| Japan | 63.9 | 69.0 | 73.3 | 76.9 | 79.5 | 80.5 |

| UK | 69.2 | 70.8 | 72.0 | 74.0 | 76.4 | 77.2 |

| France | 66.5 | 71.0 | 72.4 | 74.7 | 77.5 | 78.1 |

| Germany | 67.5 | 70.3 | 71.0 | 73.8 | 76.2 | 77.4 |

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of

the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision

and World Urbanization Prospects: the 2001 Revision (http://esa.un.org/unpp).

Most likely, there were two factors that played their role in this respect:

demographists have long established a link between women's nutrition during

pregnancy and children's nutrition during their first years with the average

height of a new generation and the life expectancy rate. As concerns the age

cohorts born between the 1920s and early 1950s, these indicators appear

substantially worse than those of the preceding and subsequent generations. The

risk that a man born in the mid-1920

’s, when the overwhelming majority of births fell on free peasants' families,

would die at the age of 30-40 was roughly half of that of a child born between

the late 1940s and early 1950s. It was only in the mid-1950s that these indices

showed some improvement[12]. The connection between such destinies with

collectivization and World War II is obvious.

Table 11. Consumption of alcohol per head (for residents aged over 15 years old)

in ethyl alcohol equivalent between 1960 and 2000 (liters)

| Years | Country |

||

| Russia | France | Germany | |

| 1960 | 4.88(2) | 32.62* | 10.71* |

| 1970 | 10.38(2) | 33.87 | 15.11 |

| 1980 | 13.40 | 33.34 | 16.18 |

| 1990 | 7.09 | 22.60 | 14.67 |

| 1999 | 10.80 | 19.87 | 12.99 |

* 1961

Source:

1. If not stated otherwise: http://www3.who.int/whosis. WHO Statistics, Global Alcohol Database.

2. Estimated (based on the data of Goskomstat,

review ”Naselenie i obschestvo”, № 19-20 (May 2001) http://www.demoscope.ru.)

Source:

1. If not stated otherwise: http://www3.who.int/whosis. WHO Statistics, Global Alcohol Database.

2. Estimated (based on the data of Goskomstat,

review ”Naselenie i obschestvo”, № 19-20 (May 2001) http://www.demoscope.ru.)

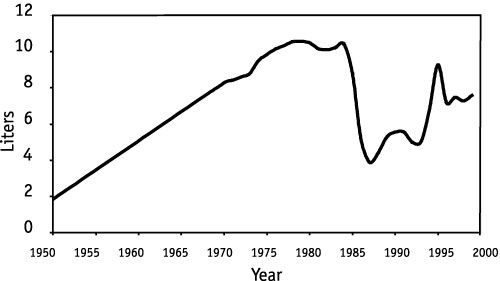

Another factor is a country-specific environment of the mass alcoholisation

among Russia's population in the 20th Century. As the data presented in Table

11 shows, Russia total alcohol consumption per head, while substantially behind

France, is close to that of Germany. The distinctiveness of Russia's situation

however is not in the volume of consumption per head but in its style, which is

characterised by the prevalence of strong drinks, intemperance, and a

widespread habit of drinking in the workplace. At the same time, this is not

only a Russians' trend

– papers on the history of alcoholism and alcoholic behavior in Germany in the

late 19th Century expose similar challenges facing that country with those

facing Russia in the 20th Century[13].

In Northern European countries, the consumption of alcohol was considered to be

compatible with economic activity in the agricultural sector

– it was, after all, one way of retaining body warmth not to mention its purpose

as a social lubricant and a source of additional calories. In the mid-19th

Century, having left his village for a city and found a job at a factory, a

German peasant would keep on preserving the tradition he had adopted in his

village. The custom of a mandatory bottle of vodka as a pass for an apprentice

to his new collective; rejection of a member of the collective who does not

contribute to collective feasts

– these customs mirror well known realities of German life in the late 19th

Century. The workers' struggle for the right to drink at work formed one of the

German working-class movement's major demands.

It was only by the late 19th Century that Germany had reached a level of

development similar to the one seen in the USSR in the 1930-50

’s, when the situation began to change, and both employers and trade-unions'

embraced ideas of abstinence at work, replacing it with a happy-hour at the

local beerstube outside the factory's walls instead.

This transition was never noted in the USSR. Against the background of

uravnilovka (equal labor compensations that everyone was entitled to), a weak

sense of communal responsibility, the absence of an initiative

in setting some socially acceptable norms of alcoholic behavior characteristic

in the early industrial stage, the mass alcoholism problem was aggravating

further. Moreover, it significantly contributed to the discontinuation of the

rise both of the average life expectancy and the growing gap between men and

women's average life expectancy. The extrapolation of the data presented in

this chart in commonly known data on the change into men's life expectancy

between the late 1980s through to early 1990s (see Fig.3) exposes a connection

between these particular indices and the fiasco of the Gorbachev's anti-alcohol

campaign (see Table 12).

Fig. 3

Consumption of alcohol as an absolute alcohol equivalent per capita in Russia in 1950-2002

Consumption of alcohol as an absolute alcohol equivalent per capita in Russia in 1950-2002

Source:

Demoscope, №19-20, May 7-20, 2001. (http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/019/tema01.php)

1 BSE. – М., 1950, vol.2, p.118,

http://optimalist.narod.ru/bro01.htm (the data on 1950)

Demoscope, №19-20, May 7-20, 2001. (http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/019/tema01.php)

1 BSE. – М., 1950, vol.2, p.118,

http://optimalist.narod.ru/bro01.htm (the data on 1950)

Table 12. The life expectancy of a Russian (the average life expectancy at birth) from 1950 to 2000

| Years: | Life expectancy (years) |

| 1950-1955 | 60.5 |

| 1955-1960 | 62.5 |

| 1960-1965 | 63.3 |

| 1965-1970 | 64.5 |

| 1970-1975 | 63.8 |

| 1975-1980 | 62.7 |

| 1980-1985 | 62.6 |

| 1985-1990 | 64.9 |

| 1990-1995 | 60.8 |

| 1995-2000 | 60.2 |

Source:

Population division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: the 2001 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpp

Population division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: the 2001 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpp

It is safe to assume that had the social cataclysms of the 20th Century, i.e.

the earlier than average women's accession to employment and the strong-rooted

alcoholic traditions of the early industrialisation stage, not taken place

Russia's population would currently have been abound 300 million (assuming that

Russia's share of the global population stayed at its 1913 level).

The leading countries of our time have only a vague vision of their future and

the long-term challenges they face. They created many of their important

institutions and establishments meant to address a certain set of circumstances

only to see those circumstances alter dramatically in the years ahead. Today,

some of the key structural challenges facing the nations of Western Europe,

North America, and Japan are directed towards securing the sustainability of

their pensions, health care and education systems. The latter were developed in

the conditions of a young populace, seemingly vast opportunities for increasing

tax revenues, and modest respective expenditures in GDP. The situation has

changed radically in 50 years of post-industrial development. And the leading

nations are now realising that fundamental strategic reforms are difficult to

implement in mature, stable democracies.

Russia must analyze the challenges facing developed nations not for a blind

replication of Western solutions but for carefully adjusting Western

experiences to Russian specifics and ensuring that a possible problem is

addressed before it entrenches and a needed reform is overdue. A. Gershenkron

argued that both Russia and the whole world had paid a high price for the

belated emancipation of the Russian peasantry[14], for Russia's belated start

of modern economic growth and the backwardness from the leading Western

European economies in which it resulted. It is ever more important then to take

advantage of the earlier beaten track: that is, to profit from both mistakes

those of our own and those of others'.

3. There is, of course, a group of countries that started modern economic growth

notably later than the leaders, but managed to catch up with them. The shining

example in this respect is Japan that had started its economic growth

practically at the same time as Russia did and managed to enter the group of

leaders by the 1970s.

4. As emphasized by A. Maddison. See: A.Maddison. Dynamic Forces in Capitalist

Development. A Long-Run Comparative View.

– Oxford- New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. P 15.

5. He was keen to explore how the catch-up development countries, less developed

compared with the Netherlands and the UK and the countries of continental

Europe could introduce such changes to the system of their national

institutions and their economic policies which would allow them to reach the

Dutch level of development.

7. A characteristic example in this respect is Prof. V.I. Grinibetsky's paper

'Poslevoyennye perspectivy russkoy promyshlennosti (Post war prospects of

Russia's industrial sector) that had a serious impact on development of the

GOELRO (the nationwide electrification) plan in the Soviet Union. The author

uses an analysis of the difference in Russia's fuel balance from those of more

the developed nations as one of the starting points.

8. Table 3 can form a basis for overly optimistic conclusions on a gradual trend

towards a reduction in the distance between Russia and the leading nations.

However, it should be taken into account that in the early 1950s both Germany

and France's indicators were still under a strong impact of effects of World

War II.

10. The data on Spain is provided because that country's path of demographic

transition is close to Russia's.

11. According to the annual data of GKS of RF, it was the period between 1965-66

when the life expectancy rate reached its peak in Russia. See: Demographichesky

ezhegodnik Rossii. M., 2001.

12. See: S.Zakharov. Kohortny analyz smertnosti naselenia Rossii (dologosrochnye

I kratkosrochnye effecty neravenstava pokoleniy pered litsom smerti)//Problemy

prognozirovania, 1999. # 2/ P 114-31.

13. J.C.Roberts. Drink and Industrial Discipline in Nineteenth-Century Germany.

The Industrial Revolution and Work in Nineteenth-Century Europe. London-New

York, 1992. ?. 102-124.

14. A.Gerschenkron. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective.- Cambridge-

Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1962.